Reposted from Style Weekly

BY EDWIN SLIPEK

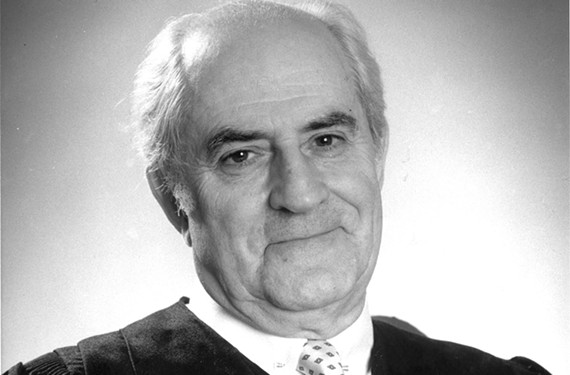

Judge Robert H. Merhige delivered many landmark decisions from the courthouse on Bank Street in Richmond, including ordering dozens of public schools to desegregate.

When the name of Robert Merhige came up in casual conversation a few years back, Al Calderaro, a Richmond real estate appraiser and history aficionado, was surprised that a friend knew so little about the federal judge who’d ruled on numerous marquee cases during the 1970s and ‘80s while serving on the U. S. Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

“You ought to,” Calderaro chided her, “He was responsible for you being one of the first female graduates of the University of Virginia.” The reference was to Merhige’s 1970 order that the school admit women.

That brief exchange led Calderaro to make his own informal inquiry into the legacy of Robert H. Merhige, Jr., who lived from 1919 to 2005. During his storied career, the New York native, who was educated at the University of Richmond and appointed to the bench in 1967 by President Lyndon B. Johnson, delivered a broad range of landmark decisions. These included court-ordered public school desegregation, the Watergate scandal, product liability and the establishment of environmental trusts from corporate fines. Many of his rulings still resonate in Virginia and beyond.

It dawned on Calderaro: “Some people are in the middle of everything — Merhige would be a good subject for a movie.”

But Calderaro was no filmmaker, although his experiences as a sculpture major at Virginia Commonwealth University and later as part of the SoHo New York art scene had often put him on the fringes of independent productions. A friend, Richmond photographer Lee Brauer, suggested he contact Robert Griffith, a Virginia-based and award-winning documentary film director. Griffith’s film “Lillian” won a special award from the Sundance Film Festival and “Seasons with Brian and Julia,” broadcast on public television, follows the life of Mathews County farmers.

With Griffith on board as directing producer and co-editor, Rodney Smolla, dean of the Delaware Law School and former dean of Richmond’s T.C. Williams School of Law, was invited to join the team. He developed a 28-page working film script in just two weeks.

“He’s a professor of law,” Calderaro says of Smolla, “There’s a lot of legal language that he communicates so clearly.”

Producer Al Calderaro, left, and director Robert Griffith are the prime forces behind the upcoming documentary on federal Judge Robert H. Merhige. – SCOTT ELMQUIST

Scott Elmquist

Producer Al Calderaro, left, and director Robert Griffith are the prime forces behind the upcoming documentary on federal Judge Robert H. Merhige.

“But the project is not strictly script-driven,” Griffith says of the film’s development that should culminate with an hour-long documentary in fall 2018. “It’s organic — you start layering the cake.”

Those layers are being formed from filmed interviews with colleagues, former clerks and others who knew the highly personable judge. Among the 17 interviewees in the can thus far are former Virginia governors, A. Linwood Holton and Gerald Baliles, such lawyers as Richard Cullen, chairman of the McGuireWoods law firm, and criminal attorney David Baugh, as well as Merhige’s former law clerks.

Federal judges Robert E. Payne and J. Harvey Wilkinson also have been filmed. Says Calderaro of the latter interview, “Although they were polar opposites in many ways, Judge Wilkinson said of Merhige: `I still miss him because of his personality.’”

“I thought there would be some redundancy in the responses of who we filmed,” says Griffith, “but that didn’t happen. There is a thread of continuity with everyone we’ve talked with — that was the fairness with which the judge ran his courtroom and the quality of what a human being he was.”

Calderaro and Griffith have established the American Documentary Film Fund, a nonprofit company that includes on its board former Merhige associates, civic leaders such as Jay Barrows and Andrew Clark, and cultural forces Vince Gilligan of “Breaking Bad” fame and former VCU School of the Arts dean Joe Seipel. The group is working with Virginia Organizing, a Charlottesville-based nonprofit focused on tackling social injustice through local empowerment. A significant amount of the film’s $460,000 budget has been raised with grants from people such as Pamela and William Royall, and law firms Hunton and Williams and McGuireWoods. Among supporting groups are the Mary Morton Parsons and Virginia Sargeant Reynolds foundations. Calderaro says that while editing is already well underway there are half-dozen or so interviews to be conducted and funds still to be raised.

For Calderaro, the goal is clear. “The Constitution is the foundation of our country, what the Founding Fathers did is a miracle and our legal system is the driver,” he says. “It is important for people to know more about the legal system and what lawyers do — it’s the glue that holds our country together. What’s been forgotten is that there are people out there who have said, `Let’s work together for the good of the country.’ Judge Merhige was the embodiment of all of this.”

“It’s timely,” Griffith says. “It is especially needed today to have an understanding of the law.”

“He really loved people,” Calderaro says. “He never lost his connection to people.”

One of the people filmed for the documentary recalled a trial where Merhige sentenced a man to prison for two years for tax evasion. There was a sharp emotional outburst by relatives as the convicted was led to jail. The judge was hustled back to his chambers, visibly shaken. Someone asked him, “Are you OK?”

“You never get used to it,” Merhige reportedly replied. “You never forget that these are people.”

“If we get just five or 10 law students who see the film to want to be like Judge Merhige, it’s a success,” Calderaro says. S